Los Angeles Kings Beat Winless Utah Mammoth in Idaho – The Hockey Writers Los Angeles Kings Latest News, Analysis & More

October 1, 2025

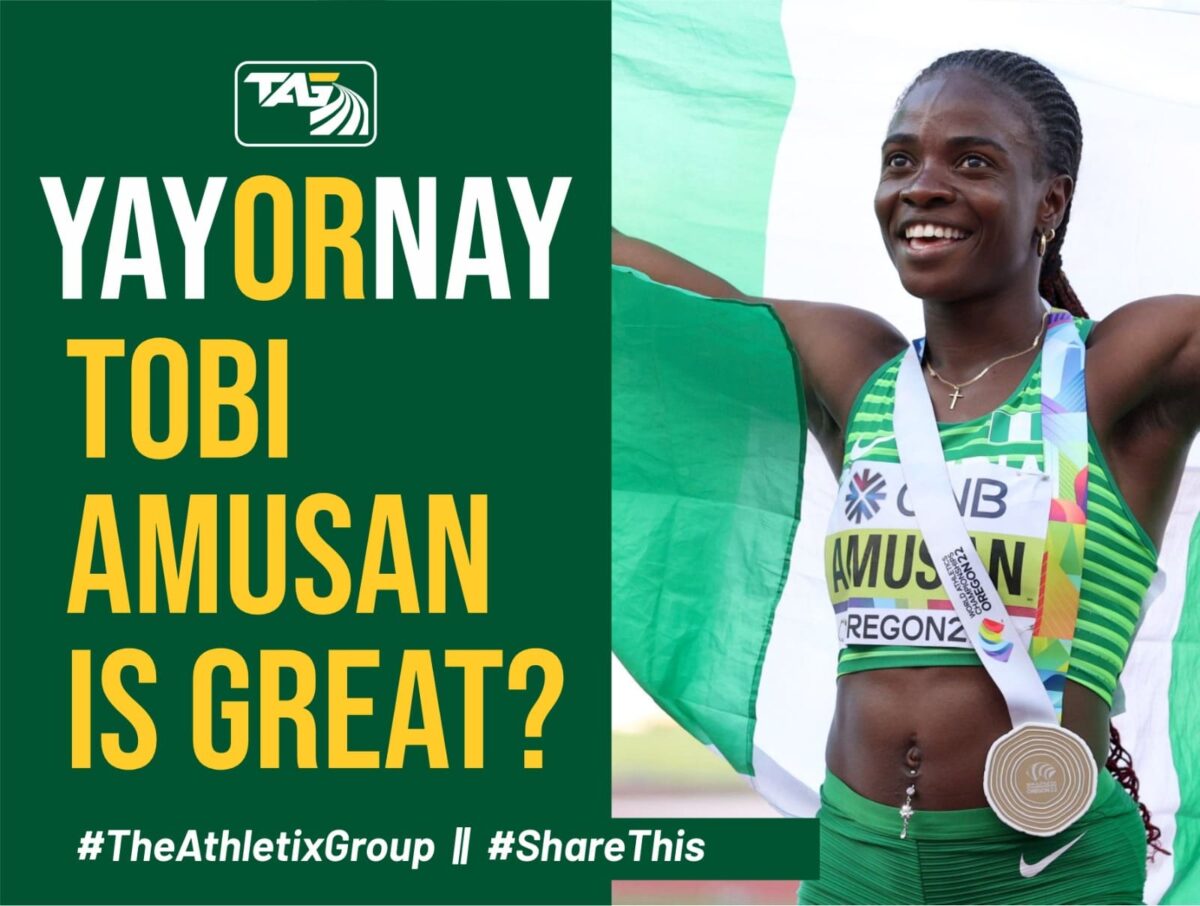

AW promotion.

Artificial intelligence is no longer something athletes talk about in the future tense. It is already part of modern track and field, from the GPS units clipped on to sprinters during warm-ups to the video tools coaches use to break down a hurdler’s stride pattern.

Now, this shift isn’t just about collecting more numbers for the sake of it, but also about making training smarter, recovery faster, and race-day strategies sharper.

Smarter Training on the Track

A few years ago, most sprint coaches still relied on stopwatches, video replays and lap splits. Now, AI-powered wearables can measure ground contact time, stride length, and even the subtle asymmetry between a runner’s left and right legs. That’s useful because inefficiencies that were once only spotted in biomechanics labs can now be flagged during a normal session.

A 2025 study on sprint performance showed how algorithms analysing hip and knee angles could predict when athletes were losing power midway through a rep.

Tools like Motion-IQ, which was tested by elite sprint groups in the US, let coaches film a training run on a phone and instantly see stride efficiency reports.

Talent ID is also changing, with AI systems analysing junior athletes’ running economy and oxygen uptake patterns to flag those who might thrive in endurance events before their results show it.

Recovery and Injury Prevention

If smarter training helps athletes get faster, better recovery keeps them on the track long enough to use it. AI has become central here, too. Systems now pull together sleep data, heart-rate variability, and training load to give daily readiness scores.

What makes this different is that it doesn’t just spit out a generic number. AI can track how your recovery score links to the risk of a hamstring pull in sprinters or stress fractures in distance runners.

A review of injury prediction methods in 2024 showed AI-driven models outperform traditional monitoring because they can weigh thousands of micro signals together.

Wearable textiles with built-in strain sensors are even being tested on middle-distance runners, picking up shifts in breathing patterns and muscle activation that suggest fatigue long before athletes feel it.

Professional squads have already acted on this. In the run-up to the Tokyo Olympics, several national federations used AI to plan tapering phases more precisely, and more recently, European clubs have trialled AI load-management tools to reduce soft-tissue injuries during long training blocks.

Race Strategy in the Age of AI

AI has also moved beyond practice and into race-day strategy. Middle- and long-distance running has seen the most obvious impact. Pacing models now crunch past race data, physiological markers, and environmental factors like wind speed to suggest split strategies. Instead of guessing, a coach can simulate what happens if their athlete goes out two seconds faster through the first kilometre or sits back and saves energy for the last lap.

Fans often look to find sports forecasts at a pro level, but similar predictive tools are now in the hands of athletes and their coaches. However, it’s not just for predicting who will win, really. They use it to plan how to use energy efficiently against different opponents.

The 2019 INEOS 1:59 Challenge, where Eliud Kipchoge ran the first sub-two-hour marathon, made this visible. His team used advanced models to set pacer rotations and kilometre splits, ensuring his energy use was as even as possible, and it showed how AI-informed planning can push human performance to the edge of possibility.

Marathoners today are already experimenting with AI pacing apps that give live feedback on whether they are likely to blow up in the second half, and track athletes in championship races are using simulations to decide whether to cover a surge or let it go.

Where the Limits Still Are

As much as AI has expanded what is possible, it still has blind spots. Models can misread data, overfit to past results, or flag risks that never actually materialise. An over-reliance on predictions can also lead to ignoring how an athlete feels on the day.

A perfect algorithm doesn’t matter if a 1500m runner wakes up with a sore Achilles or a sprinter feels sharper than the data suggests.

Data privacy is also a growing concern. Biometric data is deeply personal, and questions about who owns it (athletes, coaches, or federations) are not yet settled. Access is another issue. Wealthy programmes can afford advanced systems, but smaller clubs or athletes from developing nations may be left behind.

Conclusion

AI in athletics will likely be applied more in everyday practice. Generative AI is already being tested to create adaptive training plans that change automatically if recovery markers are low. Then there are also augmented reality glasses and earbuds that are being trialled to provide real-time cues on stride mechanics during training runs.

When it comes to specific sports events, the International Olympic Committee has also begun exploring AI to support talent scouting and even judging in field events. If adopted, this could change how officials measure fouls in long jump or monitor relay changeovers.

So, the stopwatch, once the main symbol of track and field coaching, now has a partner in the algorithms running quietly in the background. The athletes and coaches who can use both in balance are the ones most likely to benefit in the years ahead.