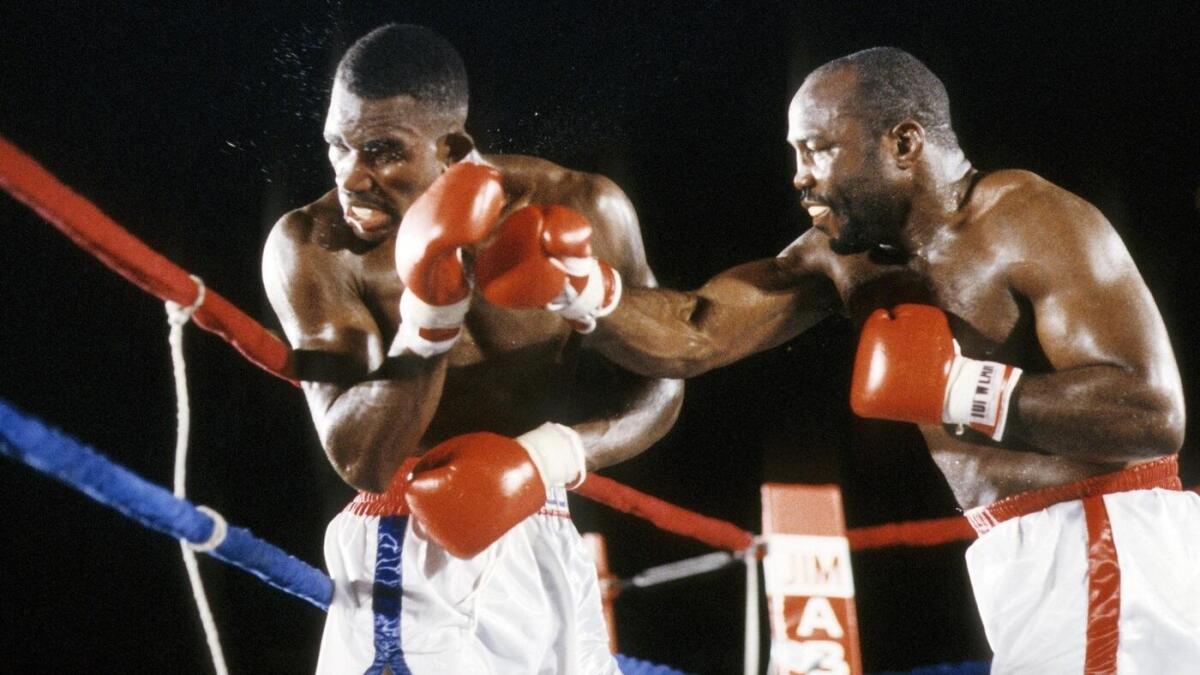

Two-division champion, Boxing Hall of Famer Dwight Muhammad Qawi dies at 72

July 29, 2025

Canadian Open: Briton Emma Raducanu reaches second round as Katie Boulter exits

July 29, 2025

Keeping Pace: Hope And Change – Time To Confront Horse Racing’s Problems originally appeared on Paulick Report.

Paulick Report: Let’s start at the end. There is always some lag time between the moment an author finishes writing a book and the moment the book is published and released into the world. The narrative in your book, “Death of a Racehorse,” ends in the spring of 2024 so my first question to you is: What’s happened in the past 15 months in U.S. horse racing that you think has been particularly significant? What’s happened during that time that would make it into the updated, paperback edition of your book?

Lillis: Great question. There were a few things that have happened since we went to print that I wish I had been able to cover in the book. One of them was the situation at the University of Kentucky lab that led to Dr. Scott Stanley’s dismissal. He has obviously disputed the findings, and I would have liked to have been able to do some deep reporting on that episode. There’s a reference in the book, but the HISA decision had only just become public in the final days of editing and so there was no time to do more.

I also think I would have given a bit more attention to some of the rule changes that Louisiana has tried to put into place, which I think emphasizes how bifurcated and at war with itself racing is right now.

Paulick Report: You’ve now had all this extra time since the book went to print to absorb what’s happening with the HISA Authority and its law enforcement arm, the Horseracing Integrity & Welfare Unit. What are your impressions of the work of federal racing regulators over the past 15 months or so? What have they gotten right? What have they gotten wrong?

Lillis: To me, the biggest story of the opening days of HISA is that it is not, in fact, a national authority. Because of the ongoing litigation, which you have covered closely, the sport operates by entirely different rules in some states. So while there has been what appears to be tremendous improvement in fatality statistics in HISA-governed states, that has not held true in states where the authority is not in effect. The industry has rightly touted those improved figures, and they do offer a powerful advertisement for HISA.

But personally, I’m skeptical that folks outside of the industry differentiate between HISA states and non-HISA states. If part of the goal is to reassure would-be fans, bettors and state and national-level regulators that the sport is doing everything it can to safeguard horses bred and used for this purpose — and that it should therefore be permitted to continue and supported with wagering dollars — that goal has not yet been met. I recognize that’s not HISA’s fault, of course, but I think it’s the reality of having a divided industry.

Paulick Report: A friend of mine who is prominent in horse racing in the U.S. said he loved the book but was disappointed in one way. He said you didn’t write enough about what he called “the economics of horse racing” and about the “transition of purses being generated by bettors versus fee legislated transfer payments from casinos.” The cost of everything is up — especially in the past few years — but in some jurisdictions the purses haven’t risen nearly as high or at all. What did you learn from researching and reporting the book about the “economics” of the sport? What should we all be paying attention to?

Lillis:‘ I will confess the broader business model underpinning horse racing was beyond the scope of this project, which focused primarily on the medication and breakdown issues, and the impact they have on racing’s sustainability — both ethically and financially, since we understand there to be a clear link between those two issues and the sport’s economic viability. That said, it was clear to me through the reporting process that there are other serious structural challenges facing racing from a financial perspective.

The fact that the sport relies on casino revenue to fund purses — what the New York Times controversially termed “subsidies” — is in my view one of the biggest strategic risks to racing in the long term. There is no inherent link between these two businesses to guarantee that state legislatures will continue that arrangement in perpetuity. The decoupling crisis in Florida earlier this year is a prime example of the shaky ground racing is standing on, and from the outside, it was clear the industry was slow to respond to the threat. It seems to me the sport has two choices: start from scratch and come up with an entirely new, sustainable way to fund purses — or find a better way to compete with other forms of sports wagering so that racing “pays for itself” through wagering on horse racing.

(article continues below)

Paulick Report: There were a lot of things I liked about the book. At the top of the list was the way in which you identified and explored the many contradictions and inconsistencies in the horse racing industry and the inherent conflicts of interests within it. I think this is especially true of the work of state racing officials. What did you learn about the work of state racing commissions during your research and reporting for your book that you didn’t already know or suspect? Did anything surprise you? And how do you compare the work of state regulators versus the new federal regulators embodied by HISA and HIWU?

Lillis: Well, I should say right off the bat that I’m the daughter of a state regulator — my mother was the chairman of the Virginia Racing Commission when Colonial Downs was built, so I’ll confess a little natural bias towards regulators. When I was 16 and walking hots, she used to ask the stewards to interview my dates, which was probably an abuse of power — but a very effective one! I suspect Bill Passmore put the fear of God into a few of them.

Funny stories aside: One of the biggest shocks to me was that there are states that allow commissions — and even worse in some cases, commission staff — to own race horses. I hadn’t known that before, and that arrangement of course offers the opportunity for some pretty shocking conflicts of interest.

There also were a number of instances that I cover in the book that suggested an entirely too-cozy relationship between the regulators and the regulated that I largely chalked up to the fact that many state regulators are, themselves, old racetrackers — or have developed what folks in the State Department call “clientitis.” To a certain degree, this arrangement makes sense: Former riders and trainers, etc. have the expertise and the nuanced understanding of the animal and the industry to do the job with care and attention.

At its best, that system works very well. But of course, it can also lead to a permissive environment in which regulators are exercising too much discretion in enforcing the rules. I write in the book that the wide degree of latitude that state commissions have had in the past has contributed to an environment of distrust in racing, where many racetracks don’t believe that penalties are meted out fairly. (You hear it all the time: “So-and-so trainer is treated with kid gloves in XYZ state because he fills races,” for example.)

It’s an obvious answer, but consistency across jurisdictions is among the most important things that HISA is trying to accomplish. Standardizing the labs would top my personal list — because for the first time, it promises to close a loophole. In theory, trainers will not be able to use more medication in one state than another simply because the testing is less sensitive there — nor will they be caught by surprise if their routine practices in a state where the lab’s equipment is calibrated differently, which has never created a problem for them before, suddenly earns them a positive test in another state.

Paulick Report: Last question. You are appointed U.S. Commissioner of Horse Racing. You have great power. Give me the first three things you’d do for Thoroughbred racing and why.

Lillis: I’m beating a dead horse at this point — pardon the expression — but I would ensure that every state in which there is live racing operates under the same regulatory schema. I’m not specifically endorsing HISA here as much as I would be mandating true uniformity across the industry in this country.

The second big “magic wand” thing would be to bring the breeding and sales industry underneath a common regulatory structure that includes not only how these animals are raised but also likely some restrictions on the stud book itself to ensure the durability and longevity of the breed, which I firmly believe to be a welfare issue. As the industry is structured now, it often leaves trainers (and tracks) holding the bag for decisions that were made with an animal long before it ever came into their hands. Until the sport takes a shared responsibility for the husbandry of individual animals across their entire lifespans, I think it will both continue to fight amongst itself and struggle to resolve the public perception challenge it has surrounding welfare.

The third and biggest thing is more conceptual and harder to mandate with a single wave of the wand. In the book, I call for a cultural change to address the gap between how racing’s consumers view the animal — akin to a “pet” — and how the industry treats the animal: as a kind of amalgam of “livestock,” “financial asset,” and at times, “commodity.” Unless racing can close that fundamental gap — which isn’t a matter of a single regulatory change, but rather requires a host of lots of small changes — I think it will struggle to maintain its social license to operate, putting its survival in the long run into question.

Notes

Measure your track, people. One of more critical (and obvious) ways in which federal racing regulators have made the sport safer for racehorses is a new requirement that Thoroughbred track operators during a meet must measure the racing surface each day, at all quarter-mile markers and at different distances from the rail. The idea is to track moisture content and cushion depth and other factors that might signal a track is less safe than it should be. I suspect that some of the track maintenance crews which have to take these measurements consider them a nuisance or, worse, a waste of time. But it’s not busy work. It’s imperative.

That’s the background. Now, here’s the story of Jack Thistledown Racino, near Cleveland, which has been in and out of compliance with these track safety requirements. Thoroughbred Daily News’ Dan Ross posted a strong piece about the problem on Friday. “Some of the smaller tracks just struggle to keep up,” says the director of the lab to which the samples are supposed to be sent. Whether that’s because there aren’t enough workers to perform the job, or not enough workers who know what they are doing, is just one of the challenges that tracks and HISA officials face. Either way, there’s no excuse for the failure to take these measurements.

Not an easy job. The new chairman of The Jockey Club,* Everett Dobson, will make his inaugural address later this week at a round table discussion in Saratoga Springs. Even apart from the open questions about the legal future of HISA, The Jockey Club and Thoroughbred racing have a bunch of fires to put out. Contraction. Wagering. The social license. Some of these fires are larger than others, right? And sometimes it must seem like the sport’s firefighters aren’t always focused on the same blaze. Paulick Report’s Carter Wilkie offered some smart context on Friday in a piece about Dobson’s arrival at the head of the organization.

Wilkie wrote: “Dobson, a telecommunications industry executive and minority investor in 2025 National Basketball Association champions, the Oklahoma Thunder, will face a different playing field from the NBA, where stakeholders speak collectively with one voice. Racing’s decision makers are diffused across competing state jurisdictions, track operators, and horsemen’s groups, all of which are incentivized to protect the status quo as it benefits their narrow interests, making alignment rare for the health of the industry’s interdependent ecosystem.” I am looking forward to Dobson’s speech and you should be, too.

Good for the USTA for passing along this story about a former athlete, Cordon Harris, who got a second chance after prison and is now working along the backstretch at Northfield Park, a half-mile harness track in Ohio. And good for the folks at TheStable.ca, a Canadian fractional ownership group led by harness trainer and driver Anthony McDonald for giving Harris that second chance. Every year, it seems, there are a few stories that pop up in mainstream media chronicling the ways in which horse care and treatment, including racehorse care and treatment, helps rehabilitate prisoners or the formerly incarcerated. It’s something the sport does well.

And good for Michelle Crawford and all of the other connections, past and present, of Homicide Hunter, who is the world’s fastest trotting horse. He’s 13 and retired and now carries the water for a horse adoption operation in New Jersey called MMXX Standardbreds. Paulick Report’s Lillian Davis wrote a nice piece last week about retraining the horse for under-saddle shows, and the organization, which has placed about 275 Standardbreds into their forever homes. “I think, in the horse community, in the riding community, which is who we try to target, they don’t realize that Standardbreds can do things like show and win,” said MMX Standardbred owner Molly d’Agostino. Amen, Molly.

(Disclosure: The Jockey Club is a sponsor of the Keeping Pace column)

This story was originally reported by Paulick Report on Jul 28, 2025, where it first appeared.